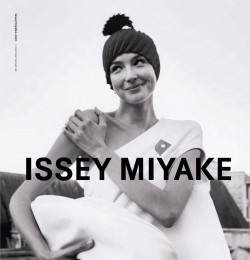

Issey Miyake

Paris, 75004

France

About

founded by

Issey Miyake

belongs to

Issey Miyake

about

In 1971 he founded the Issey Miyake Design Studio in Tokyo. He also opened a boutique at Bloomingdales in New York.

During the 70's while still based in Tokyo, Miyake began to show his collections twice a year in Paris and they rapidly became fashion shows which no fashion addict could afford to miss.

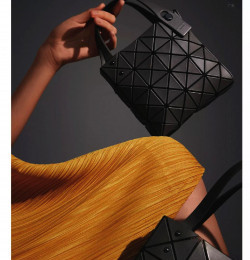

In the late 80s, he began to experiment with new methods of pleating that would allow both flexibility of movement for the wearer as well as ease of care and production. This eventually resulted in a new technique called garment pleating and in 1993's in which the garments are cut and sewn first, then sandwiched between layers of paper and fed into a heat press, where they are pleated. The fabric's 'memory' holds the pleats and when the garments are liberated from their paper cocoon, they are ready-to wear.

The Look

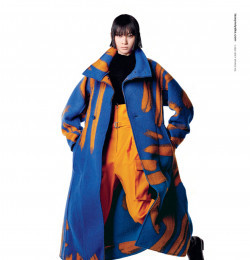

Miyake's skill with fabric is rooted in his knowledge of traditional Japanese fabrics and fabric-production techniques. The ascendancy of denim in the sixties and seventies turned his attention to Japanese workwear fabrics: ticking stripe, heavy cottons, quilting. These he incorporated into his work both in their original form and in wonderfully elaborated forms, waffle textures, heavy coarse weaves, rich seersucker effects, wrinkled, crinkled, primitive pleating and occasionally smocked.

Combined with Miyake's sophisticated colour sense, the effect of all this sensuous texture was completely fresh. Textured fabrics when employed by other designers, tended to be conventionally rich - velvet, plain, panne or printed, brocade, damask, corduroy or applique work, embroidery or lace, nubbled or hairy tweed. Even when used in fresh unexpected ways other designers cannot compete with the fabrics Miyake has developed, which respond well to being intricately cut, seamed, darted and fitted. This is consistent with his vision. He says " I like to work in the spirit of the Kimono, between the body and the fabric there exists only an approximate contact."

He does not use the kimono itself as many Western designers do, to add a touch of exoticism. He merely borrows its attributes of ease, adaptability and respect for the fabric and the patterns and shapes in space with it can create when the body moves.

If he sounds serious about his design philosophy, we he is. But he also has a rich sense of humour which contributes substantially to his famous charm. He loves to make extravagant statements when he sends his models down the runway in shiny fibreglass breastplates, or perky nipples or polished wickerwork torso cages shaped like Samurai armour.

His use of wrapping and tying techniques for the fastening of his clothes is also based on Japanese tradition. The kimono has no closure and it closed by tying the obi around the waist.

He makes clothes like 18th century Buddhist priests, where patchwork rectangles were meant to suggest the humility of tatters, although they were actually stitched from the finest of antique brocades. Miyake refines and passes on the inherently Japanese vision. His loose, even formless clothes mock the perfect-toned "me decade" body, he makes fashion retrospective.